The Perfect Fantasy Manga For Game Of Thrones And House Of The Dragon Fans

"House of the Dragon," now well into its second season, has officially restored Westeros' place on the Iron Throne of television. All the insistence that "Game of Thrones" season 8 permanently tarnished interest in the franchise now look foolish, as this prequel about fire and blood has racked up acclaim. (Read /Film's review of "House of the Dragon" season 2 here.)

With it becoming ever more unlikely that the "A Song of Ice and Fire" books will receive a proper conclusion, "House of the Dragon" is working two-fold to sustain audience interest in its fantasy world. It's worked on me; after sitting out "Game of Thrones" during its initial run, the FOMA finally got to me and I'm now watching "House of the Dragon" and reading the books.

Last time, I professed mea culpa for unfairly judging comic writer Garth Ennis (creator of "The Boys," "Preacher," and more). Now, I similarly come hat-in-hand to George R.R. Martin — I am not too cool for "Game of Thrones."

If "Game of Thrones" is your speed, then I should note there's plenty of fantasy comics you'd be remiss to not read as well. (Keep in mind Martin cites comic books as a big influence on his writing career.) This time, I'd like to point you to the fantasy manga, "The Heroic Legend of Arslan." The series is set in a fantasy world modeled on ancient Persia ("Pars") — the hero is named for an ancient Persian epic — and explores old world war and politics with a similar lens as Martin does in Westeros.

If you don't consider yourself a comics/manga/anime fan? Remember that I am, and I'm currently learning the lesson of "Green Eggs and Ham" with "A Song of Ice and Fire."

The background on The Heroic Legend of Arslan

"The Heroic Legend of Arslan" began as a Japanese fantasy novel series authored by Yoshiki Tanaka. Tanaka had previously penned the space opera "Legend of The Galactic Heroes" and so, for his next project, turned to sword and sorcery. The "Arslan" novels have never been officially translated into English, but Hiromu Arakawa, creator of "Fullmetal Alchemist," adapted them into manga in 2013, which has made it out of Japan.

Arslan is the crown prince of Pars, which is at war with its neighbor Lusitania. The Lusitanians believe in only one god, Yaldaboth, and seek to conquer and convert the whole world. The first time Arslan is brought into battle by his cold father, King Andragoras III, the Pars army falls in a trap laid by mysterious Lusitanian leader "Silver Mask."

The king is captured, the Parsian capital falls, and Arslan barely escapes with the help of his loyal knight Daryun. Together, they build a small band, a fellowship you might say, to liberate Pars. Like in "The Song of Ice and Fire," the broad strokes of the story are typical fantasy adventure, but they play out in a world where material politics win the day.

Despite being set in a fictional world, the story incorporates real Persian words into its dialogue; the ruler of Pars is always called a "shah," not a king, while elite generals are called "marzbans." Distances are measured in "farsangs" and Pars is filled with "gholams" (enslaved people — to the best of my research, this word is not related to "golem," or a clay being with no free will from Jewish folklore. Interesting convergence of spelling and meaning, though, huh?)

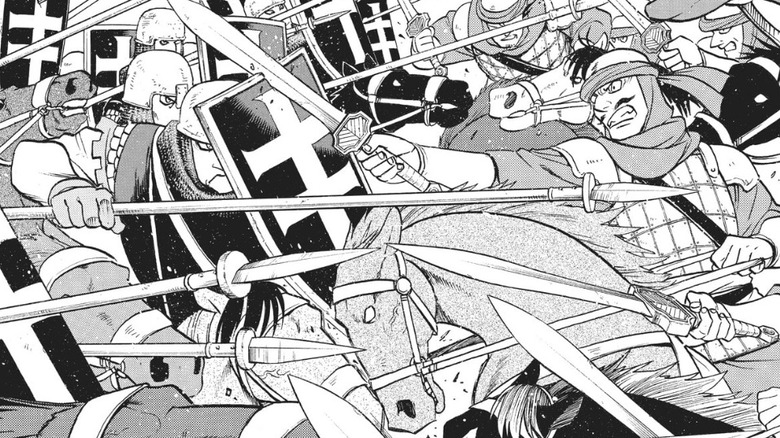

The art is similarly bound to real history. Parsian soldiers are draped in plate armor and turban helmets, while the Lusitanians wear the chainmail of the Knights Templar. (To make the crusader imagery extra obvious, the Lusitanian symbol is a two-barred cross.)

Common themes in Game Of Thrones and The Heroic Legend of Arslan

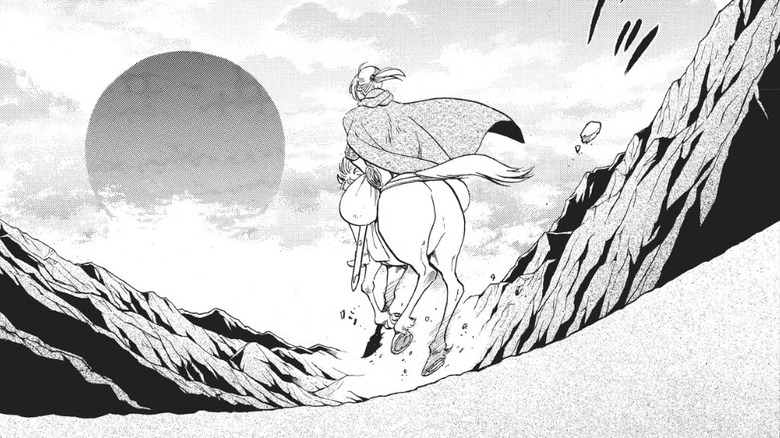

Both of these stories draw on real history, but the inspiration for "A Song of Ice and Fire" is medieval England, miles and centuries away from the Persian Empire. Martin's novels are set in forests, stone castles, and tundras; "Arslan" unfolds in deserts and mountains. While the aesthetics differ, the core stories are similar.

Both "Arslan" and "A Song of Ice and Fire" are high fantasy stories with the cloak of low fantasy ones. The overarching threat in "Arslan" is Zahhak the Snake King, defeated by the first Parsian shah Kaykhusraw generations prior. Snake King cultists survive, though, and are puppeteering Silver Mask to revive their master. Compare this to the similar threat of the White Walkers in "Game of Thrones" — while the leads are preoccupied with mortal conflicts, a supernatural menace is brewing that could sweep them all away.

Speaking of said conflicts, both stories have a deposed prince(ss) as a lead; Arakawa even draws Arslan with white hair, just like a Targaryen. He begins the story as a timid boy, but grows into an iron-willed commander while retaining his kind heart. One of his goals as shah? Abolish slavery throughout Pars (just like a certain Stormborn queen), even if, as his advisor Narsus notes, this won't win him allies among his country's nobles.

Comparing Prince Arslan and Daenerys Targaryen

Think on Martin's famous question about "The Lord of the Rings," that whether part of Aragorn's simplistically described "wise rule" included orc genocide to prevent any resurgence of Mordor's war machine. What he confronts in his writing is the logistical difficulties of ruling; it's impossible to be a hero to everyone in political court. When Daenerys Targaryen takes the slavery-based cities of Essos, she learns that freeing enslaved people requires more than the good start of killing their masters.

"Arslan" mentions how its hero will face similar problems. To be a liberator of chained people, one must deprogram their beliefs that they're only property, give them tools to live with the freedom they deserve by simply being born human, and stamp out dissent from those who once prospered under the old system of bondage.

Yet this "Heroic Legend" isn't being regressive and never suggests slavery was okay just because it was the distant, unenlightened past. A less compelling story it might come to the conclusion that changing the world is too difficult, so better to just let an imperfect status quo run its course and tinker around the edges. Not these ones, though. Ending slavery, or any systematic progressive reform, is hard — but it must be done.

What makes a good king?

In Martin's world, good men aren't always good rulers, especially during crises of succession. Martin lets his readers judge what makes a quality leader; as "House of the Dragon" co-creator Ryan Condal has noted, the biggest theme of the show and its larger franchise is that the best system of governance is one that's decided by choice, not birthights.

"The Heroic Legend of Arslan" juggles the same question (what makes a good king?) in its lead's arc and the story's conflicts; like in "Game of Thrones," different players want the same crown. As Arslan learns to be a ruler-in-exile, he leans on his advisors; he usually picks the most merciful option and needs their reassurance (or contestation) about whether that's the right choice.

The theme of rightful kingliness comes into focus when it's revealed Arslan is not the lawful prince of Pars. Andragoras got his throne by assassinating his older brother, Osroes V, and killing his nephew Hilmes — only he didn't finish the job. Silver Mask is, in truth, Hilmes (the mask covers a burn scar Andragoras inflicted), who has come to avenge his father and himself. Arslan's own father is the usurper and Arslan himself is fighting for an illegitimate claim.

Yet, while Hilmes has the laws of inheritance on his side, he's also used Pars' enemies as allies of convenience, letting the Lustianians run rough over the nation and oppress its "heretic" population. His desire to rule is selfish, unlike Arslan who has a noble heart, if not blood. Who is the better king, the one who earns it by birth or merit? The answer seems obvious to us, but not to the characters who've never conceived of a system beyond feudal monarchy. Arslan's selflessness is his strength, for it opens the eyes of those who fight beside him.

How Arslan fits in with Arakawa's previous work like Fullmetal Alchemist

Arakawa is the reason I began reading "The Heroic Legend of Arslan." "Fullmetal Alchemist" is the first manga I read (and also not a bad pick for "Game of Thrones" fans). While "Arslan" is not her original work, she does bring her own touch in presenting it. Arslan himself looks like a silver-haired Edward Elric with bigger and more innocent eyes.

"Fullmetal Alchemist" included a fictional nation named Xerxes, which like Pars was modeled on ancient Persia (its name comes from a famed Persian ruler). Her experience drawing Middle Eastern-styled castles and towns, and seeming existing interest in Persian history, made her a natural fit to realize this legend in graphic form.

The Zahhak Cult can move and teleport through shadows. Arakawa draws these blob like shadows (with enormous eyes sprouting from them) much like she did the villainous Homunculus (and his son Pride) in "Fullmetal Alchemist." Besides those serpentine villains though, there's no superpowers or magic in "Arslan." Part of what made Arakawa's action so good in "Fullmetal Alchemist" was tapping into the ingenuity of her characters, thinking how they would alchemically transmute something in the heat of battle. "Arslan" is much more grounded, depicting clashes of armies on horseback and one-on-one sword duels. Yet Arakawa's talent for drawing action scenes still shines through.

The brutal action and urgent themes of The Heroic Legend of Arslan

Arakawa's "Arslan" uses many detailed wide shots of huge formations or charging crowds; once they collide, she makes the messiness of battle feel ordered. She often favors thin rectangular panels, using them to emphasize the full sweep of a sword slamming down a man's head (vertical panel) or through his neck (horizontal panel). Her art style has always hewed on the cartoony side, which made the regular moments of gruesome violence in "Fullmetal Alchemist" all the quesier. That contrast is even more apparent in "Arslan," where every fight features soldiers having their limbs and heads severed with swords.

"Fullmetal Alchemist" is also a series about people questioning their beliefs, which fits alongside the conflicting feudal loyalties in "Arslan" and the hypocrisy of the Lusitanians. (Like real Christians, they claim their God loves all but shun those who don't believe.) Colonel Roy Mustang wrestles with what kind of leader he must be, like Arslan does, and both stories are about the obligation we all have to confront evil: "Fullmetal Alchemist" climaxes with its heroes overthrowing a military dictatorship.

We don't know yet what kind of king Arslan will be, but his legend is worth following for any fantasy fan out there.

"The Heroic Legend of Arslan" is currently ongoing. It has had 18 volumes published in America, with Volume 19 scheduled for release on July 23 and Volume 20 on November 26.