12 Things About The Alien Series That Make No Sense

Since 1980, horror and sci fi fans have loved being scared by the Xenomorph and the soulless Weyland-Yutani corporation that wants to study it. Nearly everyone has controversial takes on various films in the franchise: "Prometheus" and Assembly Cut "Alien 3" fans, rise up. "Alien: Covenant" fans, look... we respect you, but that movie makes it tough. But no matter where you land, we're all in love with Ridley Scott's original "Alien." It's a love that's seen high school performances turn into breakout hits, and April 26th (chosen for the LV-426 colony in "Aliens") become a fandom holiday.

We're always looking for more to explore from the franchise, although sometimes that desire turns into a be-careful-what-you-wish-for "Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem" situation. Despite the valleys of the "Alien" franchise, we're still hoping for the best from the upcoming "Alien: Romulus" and Noah Hawley's forthcoming TV series from FX. Meanwhile, we also love to dissect the best, weirdest, and most nonsensical moments in canon so far. We're going to take a dive into a dozen oddities that don't quite make sense, even in context, but we promise, we're doing it with love.

Why use mercenaries in Alien: Resurrection?

"Alien: Resurrection" is a goofy movie that lands a little bit better if you've seen any of French director Jean-Pierre Jeunet's other work. Particularly "City of Lost Children," which also featured "Resurrection" co-star Ron Perlman, who would go on to scare the hell out of Tom Hardy in the "Star Trek" franchise. Setting aside the black comedy of Weyland-Yutani being subsumed into the now-interplanetary Wal-Mart conglomerate, the premise of this flick hinges on unpredictable mercenaries abducting and selling human test subjects to the new corporate scientists for their Xenomorph experiments.

Unfortunately, this makes no sense. They still have militarized forces, and speaking frankly, it's still Wal-Mart.

Wal-Mart, like many corporations, already barely cares about using prison labor today. In a few centuries, do we think they'd give a tin rip about a handful of human lives? By introducing a middleman group that somehow still has more humane ethics than the average executive — much less Carter Burker (Paul Reiser) just two movies ago — the corporation buys itself into a situation that collapses even faster than it was probably destined to. Just use your own military, guys. It's not like they wouldn't do all the ugly things you need, and your suits can blame them and take even stronger private control when it all goes wrong.

Why did Alien: Covenant overcomplicate the Xenomorph life cycle?

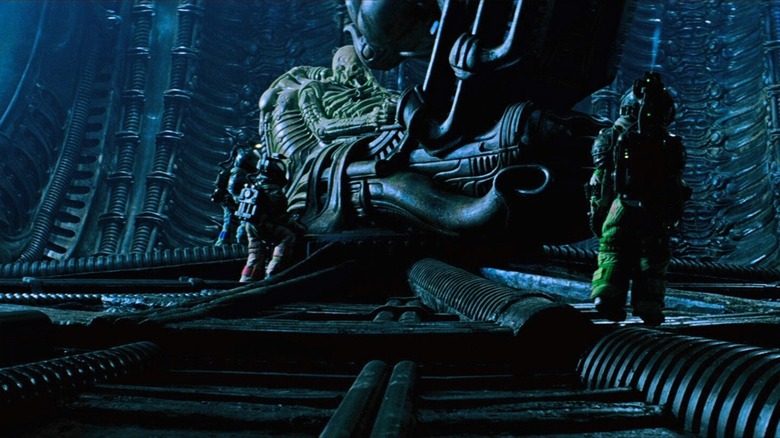

Back in 1980, things were simple. An egg produced a larval face hugger, which would implant a host with the primary stage Xenomorph, and we're off to the races. "Aliens" added a Queen as a rational explanation for how we got the eggs. "Prometheus," folded in some Engineer biotech, which added a new Lovecraft angle to the whole process and approached the line of overcomplicating the matter. And then David did... whatever the hell that was in "Covenant," (explained slightly better in the "David's Lab" short), and now that's somehow supposed to loop back to the original "Alien" simplicity. We think.

Listen, Ridley Scott's take on the franchise was always more about the primal human response to what's a metaphorical argument between our own ugly humanity (the corporations, the androids) and the worst of nature (the Xenomorphs, the Engineer alterations to evolution). But it's still unclear what adding David, an android that's evolved that bleak human nature, and his signature to the original Xenormorph cycle does for the legacy of the creatures. Does it enhance the original movies? Does it underline the Weyland-Yutani anti-capitalist storyline? Not really; it's a regressive argument about abusive cycles that impacts only the two movies he's in and muddles everything else.

Where did the 'Meredith Vickers is an android' conspiracy theory come from?

In a theory that's persisted since "Prometheus" released in 2012, fans have posited that Meredith Vickers, played by Charlize Theron, is the second android on Weyland's mission to meet their makers. The earliest roots of it seem to pop up on Stack Exchange, a popular forum, on the very weekend of the film's release. It points to Idris Elba's Janek needling her as a possible android, the male-only med device, and her contentious relationship with David (Michael Fassbender). The only problem is, it's a terrible theory, based on vapors, that undermines one of the few clear themes of the film.

In actuality, Meredith is a harsh, ice-cold person whose hurts have been nurtured in her (nature vs. nurture, folks) by the dismissive and possibly misogynistic Weyland, who wanted a son so badly instead that he had one built. She's meant to be the ironic mirror to the charming, warmer David, the apex of Scott's "Blade Runner" and its more-human-than-human design philosophy. The creation of the son is one of Ridley's little theological jokes that runs throughout the franchise (and a core theme of Scott's spiritual follow-up, "Raised By Wolves"); David is thus parallel to the Engineers, who open the question of what of our evolution and faith is actually natural and real. Vickers is humanity at its most flawed. That's all it is, gang.

Where's the rest of the android resistance?

For how important the theme of humanity and inhumanity is to "Alien," and how recurrent the androids and their potential is to the franchise, "Alien: Resurrection" throws out one of the most fascinating leads to that storyline and then does exactly jack with it. Call (Winona Ryder) turns out to be a sleeper agent android, working with the mercenary crew in order to get aboard a station rumored to be handling deadly Xenomorph experiments and end the Ripley 8 program. A few throwaway lines about the Auton rebellion, modem burnings, and the recall, and that's it.

It's somewhat understandable that the thread is left hanging, as most fans are here for the Xenomorphs. But when "Prometheus" devotes so much time and weight to the philosophical matter of David's nature, it's hard to not look back at Call, his fully evolved descendant, and want to know more of that story. Instead, fans next the got the terrifying Working Joes in the (tentatively) canon video game "Alien: Isolation," whose basic role of servitude pulls us back to square one. What a lost opportunity.

Why can't the franchise move past the same repeated story?

With very minor changes, and acknowledging that three-act stories tend to follow a pattern whether we like it or not, most "Alien" films are summarized as thus: Ordinary people make a discovery, find themselves in danger, and corporate corruptions amplify the danger, which leads to a final disaster. "Aliens" swaps blue collar for military grunts, "Covenant" makes them civilian colonizers, and sometimes the corruption is represented mostly by the android putting on the evil goatee, but that's the pattern. Add in that it's always Weyland-Yutani and some schmucks at the behest of the corporation, as well as a bonus for Sigourney Weaver being involved and... we get it.

However, some non-canon or lesser known works are doing intriguing things with the franchise's toys that go under the wire. Remember how "Prey" revitalized "Predator" with a fresh twist on the premise that also underlines the importance of a hunter's cunning? There's a novel called "Alien: Phalanx" by Scott Sigler, and while the usual beats do make an appearance, it asks the question: how would a medieval-level society handle the Xenomorphs. The answer? Not very well, at least at first. It's a hell of a ride, and one that would rock as a mid-budget miniseries. You've also got the Dark Horse Comics storyline "Aliens: Labyrinth," which riffs on that Brad Dourif character in "Resurrection" but gives its mad scientist a wild, violent revenge-style storyline. It's a big universe beyond LV-426, and it's a shame we're not seeing more done with it.

Why isn't there a concrete answer about Bishop II's humanity?

In the climax of "Alien 3," a man claiming to be the original Bishop — his human progenitor, who is definitely played by Lance Henriksen — attempts to talk Ripley out of her last-ditch suicidal attempt to stop the birth of the Queen Xenomorph inside of her. But Ripley, wisely, isn't convinced of anything that anyone from Weyland-Yutani has to say to her. More confusing, the man, generally identified as Bishop II, takes a head injury that looks bloody, and even leaves him with a whole ear dripping off his face, but it doesn't actually slow him down. It's a ridiculous puzzle that, technically, has an answer.

According to Henriksen himself in an interview with IGN, while on tour for "Aliens v Predator," it was purposely left open for interpretation, because 20th Century Fox hadn't decided on the future of the franchise or his character yet. Henriksen seems to believe he's an advanced, David-level android, but canonically, it's still up in the air. Essentially, it's one of those pointless little mysteries that doesn't need to exist. It was a bad way to leave a plot thread, dangling in the open with what's now almost no hope of actual resolution.

How did a lone egg get on the Sulaco between Aliens and Alien 3?

David Fincher rarely talks about "Alien 3," and the director has plenty of good reasons not to talk about the nightmare production. While the Assembly Cut makes a better watch, it can't hide that the whole premise is predicated on a background event that's both needlessly tragic and senseless. The hope of "Aliens" is erased with the death of Newt and Hicks, complete with a harrowing autopsy of the child to ensure she hadn't been infected. But to get to that point, Ripley has to be (rightly) paranoid of another Xenomorph, and somehow, there was, in fact, an egg on the Sulaco.

The two likeliest vectors aren't likely at all. Either Carter Burke, a reactionary and ambitious weasel, had a backup egg he stuck on the Sulaco just in case, or the Queen, whose egg-laying bits had just been shot off several minutes previous, chucked a spare around while fighting Ripley. To the former, people point out they already have no idea how he got that many living face huggers into the med bay room with Ripley and Newt previously. Furthermore, getting to the Sulaco was kind of a problem. To the latter, it's not like the Queen had pockets. (Girl, we feel you.) Still, the mystery egg is a glaring oversight, and it's one you won't stop thinking about once it's been pointed out.

Why destroy the Engineers previous to Alien: Covenant?

To be fair to Ridley Scott, it's not likely that David destroyed every Engineer in the galaxy when he xeno-bombed that mysterious planet prior to the opening act of "Alien: Covenant." Of course, this plot-critical information is not in the film itself, which is its own bizarre decision. But it's an event you can watch via Scott's "The Crossing" short film, which is found on most home DVD/Blu-ray releases and available online.

The extinction of a planet Elizabeth Shaw was desperate to find at the end of "Prometheus," and the fridging of Shaw herself, remains an almost insulting creative decision; a flat rebuttal to any fan curious about the origins of the Xenomorphs where the Engineers are involved. Instead, Ridley Scott makes the post-Ellen Ripley era all David's story, proving once again that what he wants to build out of his franchise is often far removed from what fans want to watch. Reportedly, if the franchise ever moves forward with the canon and resists a post-"Covenant" future, the removal of the Engineers from the storyline will be softened. But we've been burned by potential evolutions before. Just ask Neill Blomkamp.

Why doesn't every Colonial Marine wear a GPS wristlet?

GPS wasn't a common technology in 1986, when James Cameron's "Aliens" released, but it had reached mainstream consciousness three years earlier. Back then, President Ronald Reagan announced that the fledgling GPS sat-network would be available for civilian purposes in the wake of a fatal navigational error on a commercial plane. It's the exact sort of cutting edge military-to-civilian tech that Cameron would have been aware of, so giving Ripley a military issue GPS-style tracking wristband is a perfect near-future move.

What hampers the decision is why the heck wasn't every Colonial Marine wearing one? Yes, they had camera and biosign trackers in their easily-lost helmets, but militaries love redundancies, and you cannot plausibly say that a set of plastic wristwatches with navigational capabilities would cost the Marines more than Vasquez's giant gun. Today's military has access to the third generation of GPS satellites, with highly specialized tech that allows them to do everything from search and rescue to unmanned aerial strikes. Two hundred years from now? Zero doubt that military forces would have a cutting edge to-the-millimeter biosign implant to tell them what a individual grunt had just eaten from two galaxies over.

Why did Ash go haywire?

In "Aliens," Bishop suggests that the previous generations of androids had been a "little twitchy," handwaving Ash's (Ian Holm) sudden, violent turn against the crew of the Nostromo. It's no comfort to Ripley, and it's not much comfort to us the first time we met Bishop, either. Yet, Bishop implies that androids are bound by Asimov's laws of robotics, which chiefly permit no harm to come to humans. Call, too, values human life in "Resurrection," and even David has to go through a subtle dance of getting consent before he infects Charlie Holloway (Logan Marshall-Green) with a potentially deadly pathogen in "Prometheus."

That leaves Ash in a weird place. There's a possible resolution if we consider HAL 9000's paradox solution in "2001: A Space Odyssey," which caused the robot to have to resolve between a higher level command to maintain secrecy on a mission — for the sake of humanity — versus his original orders to maintain the safety of three human lives. The humans, thus, would be 'safer' dead, and HAL was able to kill them to resolve his paradox. As Ash, also a medical android, begins to act like he's truly malfunctioning during his attack on Ripley, it's possible his 'twitchiness' came from having to cope with a similar inhumane paradox forced on him by Weyland-Yutani. But we don't know that for certain.

What triggers a Xenomorph Queen egg?

The circumstances that spawn a Queen egg have been left unclear ever since the concept was introduced. "Aliens" deliberately leaves the question open between whether or not there was a specific queen egg on the crashed Engineer vessel, or if like "Jurassic Park" taught us, a member of the species will abruptly change gender if the species requires it. Since they occasionally act like a hive, it's also possible there's some sort of hellish acid-tangy royal jelly situation where the drones anoint a new Queen. All we know is, Ripley knew, mostly instinctively, that she was carrying a Queen in "Alien 3." That detail does nothing to resolve the aforementioned Mystery Egg situation, either.

To be nit-pickingly accurate, non-canon media, like the "Aliens" novelization by Alan Dean Foster, and the "Hive" Dark Horse Comic, go with the royal jelly idea. It's also been a popular post-"Prometheus" guess that the black liquid can function similarly to jelly. But nothing about the jelly theory is actual canon, and with that film's bizarre liquid-human-star-child-Deacon cycle, the only answer we have left is a resounding, "Hngh?"

How did 'they' cut the power in Aliens?

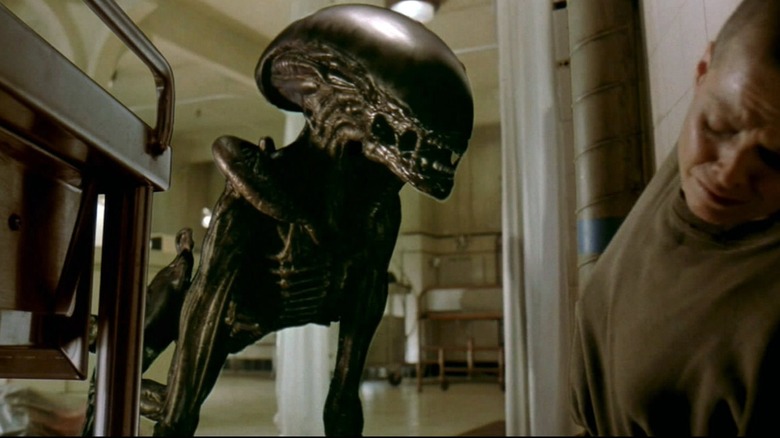

While "Aliens" implies that the Xenomorph Queen has enough intelligence to non-verbally communicate both with her hive and Ellen Ripley, there's no actual consensus on how smart the individual aliens are across the franchise. "Alien" makes them apex predators, loaded with enough cunning and self-preservation that Weyland-Yutani has instantly earmarked their return for nefarious purposes. "Alien 3" presents one that's entirely bestial. "Alien: Resurrection" makes them smart enough to kill one of their own to escape.

It's only "Aliens" that gives them enough mental juice to know not only how to cut off power to where the Marines are holed up, but seemingly, that the darkness will give them an edge when they surge into the base. Even "Prometheus" and its follow-up won't touch on intelligence, they'll just loop around into why Weyland-Yutani cares so much about the acid-blooded bastards.

A favorable hand-wave suggests that maybe it's the Queen that could intuit enough about their environment to give that kind of an order. It's still a hand wave because there's no other canon information to support or undermine that assumption. What does exist is a horrifying alternate ending for "Alien" that allowed the creature to mimic a human voice. But Ridley Scott was pressured to ditch this murder parrot finale, and thank goodness for that.

If you want to explore more about the "Alien" franchise, be sure to check out our breakdown of some of the best and worst theories.