A New Non-Fiction Book Makes Me Want To Apologize To Jurassic World

I'm not a fan of "Jurassic World." But I'm comfortable enough to know when I owe a movie an apology. And I owe Colin Trevorrow's 2015 resurrection of the beloved dinosaur franchise a big one.

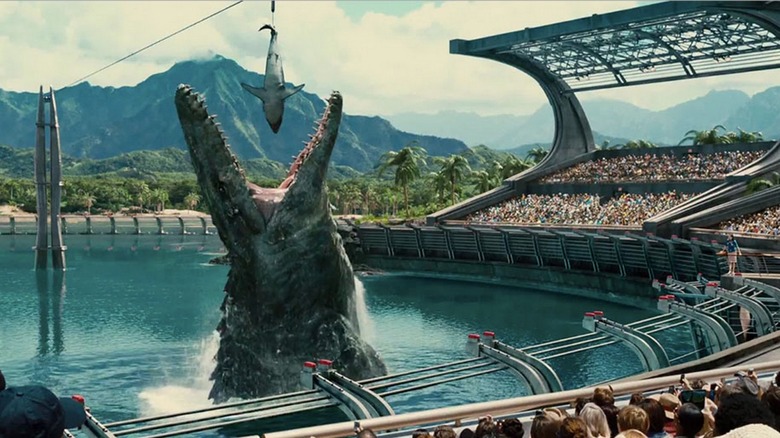

You've probably seen the movie. Taking place years after the original "Jurassic Park" trilogy, the film is centered around a dinosaur theme park that went right. Cloned dinosaurs populate exhibits attended by countless tourists. There are rides, restaurants, and merchandise. Everything does go belly-up once the plot kicks into gear, but it's firmly established that this miraculous, impossible place has been doing just fine for quite some time. Long enough that people are, well, getting bored of it.

And this proved a sticking point for many critics and viewers alike when the film was initially released. Myself included. We just couldn't possibly imagine a world where dinosaurs were back and people were ... not excited about it. That the Jurassic World parent company would need to resort to creating genetic monstrosities to boost attendance, that a new generation of visitors were just nonchalant about the staggering achievement that had been built here, seemed impossible to comprehend. This plot point was widely mocked. Eyes were rolled. I was among those who found this concept difficult to swallow, and while I have other issues with the movie beyond this element (I'm apologizing, not embracing!), this was easy to latch onto. "Haha, this dumb movie thinks we'd get bored of living, breathing dinosaurs after just a few years! How dumb!"

And then I read Adam Higginbotham's new book "Challenger" and I realized the truth: "Jurassic World" got it right. I'm sorry, "Jurassic World."

A real-life tragedy sheds light on the whole thing

Yes, I know this sounds weird. Hear me out.

Higginbotham is increasingly one of my favorite authors of non-fiction, a skilled journalist and historian who writes with the instincts of a master thriller writer. His "Midnight in Chernobyl" remains one of the best books I have ever read, a chilling, lucid, and addictive account of that terrifying nuclear tragedy (and a must-read for anyone who found themselves staggered by HBO's miniseries "Chernobyl"). "Challenger" has the same clear-eyed, horrifying style — in order to explain why the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded shortly after takeoff in 1986, he takes the reader through the entire history of the United States' quest to win the space race, examining in horrifying detail the bureaucratic missteps and malfeasance that led to the tragic deaths of seven American astronauts.

The book is incredible. You should read it. You should especially read it if you're a millennial like me, and grew up only hearing the sanitized, hand-waved version of the entire story. It's essential.

But a recurring theme throughout the book is the battle for the public's attention. The mission to build Space Shuttles, to reach the stars, is only viable if the American people support it. And their support is always a coin flip, depending on the social mood of the country or the state of the economy. Whether NASA is a massive waste of resources or a shining light guiding us to a remarkable future depends on the whims of a country prone to sudden changes in mood. Humans are fickle. Americans more so.

And that fickleness is the one thing that, in retrospect, "Jurassic World" got right beyond a shadow of a doubt.

Jurassic World was right: wonder has a short shelf life

Let me direct you to one potion of "Challenger," from relatively early in the book:

"Just as they had when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first human beings to set foot on the lunar surface some three years earlier, US TV networks carried live pictures of the Apollo 17 mission. This time, however, viewers called the CBS switchboard in frustration: the coverage had made them miss the latest developments in the hot hospital drama 'Medical Center.'"

The moon landing, the most-viewed event in human history up until that point, was still a fresh event. The most incredible scientific and engineering achievement of all time had just happened. And yet, the magic was gone. It had expired. The most incredible thing to have ever happened in human history was now an inconvenience to people who wanted to watch the latest episode of a long-forgotten medical drama. Wonder has a shelf life.

If real people in the real world were really so bored of space travel and the moon landing so soon after it captivated every single person on the globe ... well, of course they're going to be totally over cloned dinosaurs a decade after a successful theme park made it something a family could safely experience. We're not built to be amazed for very long.

So, I'm sorry "Jurassic World." I'm sorry, Colin Trevorrow. This isn't enough to make me a fan of the movie, but it is enough for me to realize how profoundly incorrect we all were when we picked on this plot point back in 2015. You knew what's up. You understood that awe is a limited time only kind of deal. And it's shame that you needed to know that.

I spoke about this on today's episode of the /Film Daily podcast, which you can listen to below: